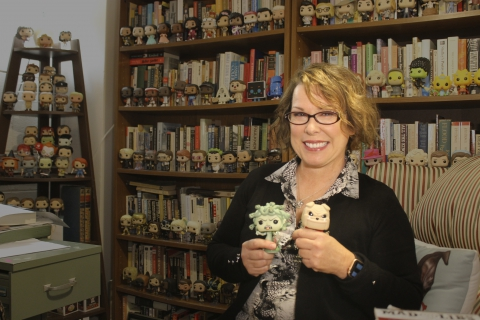

Dr. Lesa Shaul holds two of her favorite Funko Pop! figurines.

English professor’s love of literature and pop culture shines in Wallace Hall

Story: Phillip Tutor | Photo: Betsy Compton

When Dr. Lesa Shaul reclines in her chair, within arm’s reach are shelves of classic literature, the poetry of Percy Shelley, William Faulkner’s streams of consciousness, the brilliance of Robert Penn Warren. For a professor of English, the cramped space seems an oasis of calm, a few square feet bloated with printed words worthy of memorization.

But there, amid her office at the University of West Alabama, Shaul is never alone.

The whole cast of “Hamilton” is present, including a resplendent King George III. So, too, is Vito Corleone, the Kennedys, John F. and Jackie, and a toga-wearing Bluto from “National Lampoon’s Animal House.” If they could, Adele, Willie Nelson, Prince, Amy Winehouse, Billy Idol and Johnny Cash would sing while she reads. Venus Williams isn’t the only athlete in the room; joining her are Michael Jordan and Allen Iverson and a host of NBA stars. Rocky Balboa is there, along with Apollo Creed. The cast of “The Simpsons” is nearby. Daryl Dixon and Michonne and Dog from “The Walking Dead” mingle with colleagues from “The Office.” Marilyn Monroe looks exquisite, as does Queen Elizabeth II and Princess Diana.

Among Shaul’s favorites are residents of her office’s Murderers’ Row. They’re a bloody mess. Hannibal Lecter. Jason Voorhees. Patrick Bateman. Freddie Krueger. Michael Myers. Jack Torrance. And Chucky and Carrie and Pennywise.

The obvious question: Why?

“Because I’m a little into the macabre, maybe,” Shaul said.

Perhaps. But it’s undeniable that these characters of pop culture, sports and music — 213 Funko Pop! collectible figurines — are the visual stars of Shaul’s space in Wallace Hall. They’re omnipresent: on bookshelves, atop filing cabinets, guarding her office door, near her computer. There’s seemingly no room for new arrivals, which there surely will be. The sheer number of Funkos, with oversized eyes and odd facial expressions and tiny torsos, can make it hard for first-time visitors to preserve a train of thought.

They also share the spotlight with Shaul, the former director of UWA’s honors program who’s won several of the university’s top faculty honors, including the McIllwain Bell Trustee Professor Award (2016) and the William E. Gilbert Award for Outstanding Teaching (2003). But her office collection of pop-culture toy figurines is so unique, as well as so visually arresting, that separating her campus image from her decades at UWA isn’t a simple exercise.

She’s OK with that, even if the sight of a few hundred faces staring at them catches unsuspecting students off guard.

“I didn’t move the Funkos to my office until after we came back from the COVID shutdown,” Shaul said, “so it seemed to be a manifestation of some sort of psychosis I had developed during the shutdown. But only now are students actually coming to my office really with any kind of regularity.”

For what it’s worth, sharing her office with marauders and queens and movie stars wasn’t an orchestrated plan. Minus the Funkos, Shaul’s workspace is an extension of her day job, an English professor enveloped by spines of classic works. But her son was a fan of “The Walking Dead” graphic novels, which birthed a familial obsession with the television series and the acquisition of her first figurine, a likeness of Daryl Dixon, thanks to a gift from Dr. Alan Brown, an UWA English department colleague.

Shaul wasn’t yet a Funko Pop! devotee, though she found the merging of toy figurines and her preferred zombie apocalypse drama worth the child-like effort. Shaul couldn’t have only one “Walking Dead” character, she thought. If she had Daryl, she had to have Michonne. And Daryl’s pet dog named, simply, Dog. And Alpha, one of the show’s villains. And another version of Daryl. The spigot was opened. “And then people started noticing that I had these things and they would buy them for me as gifts, and I would obsessively find ones that I wanted,” she said.

Jazzed that her collection has topped 200, Shaul is adamant that “it is not quite crazy land,” and she’s probably right, given that the Guiness Book of World Records lists the largest Funko Pop! collection at more than 7,000. Students who swing by her office are often astonished, but nothing more, not even when they hear that her favorite Funko is Medusa, her head draped in poisonous snakes. “They either think I’m a weird, crazy woman or they immediately delight in trying to identify them, like, ‘Oh, that is so cool,’” she said. “And they love them for the same reason I do. It’s the little individual touches, like Miles Davis with his trademark giant glasses, and Dwight Schrute (from ‘The Office’) with the stapler and the Jell-O.”

Behind the playfulness of her office decor is a childhood story of a curious schoolgirl, an encouraging grandmother and an inquisitiveness that couldn’t be quenched.

“I loved books and I loved reading. My sister is 10 years older than I am, and so I would go for a lot of her books, which weren’t necessarily age appropriate; it was a lot of Judy Blume. I read ‘Helter Skelter’ when I was pretty young. I read anything I could get my hands on.”

— Dr. Lesa Shaul

Sand Mountain, the region of northeast Alabama where Shaul grew up, is a strip of Appalachian foothills southwest of Chattanooga, Tennessee, renowned for rocky land and small towns. Her family lived on a chicken farm near Douglas, a Marshall County burgh of less than 1,000 residents that offered a few gas stations and a drugstore, but not much else. Her grandmother taught school. When they went to town, they drove south to Gadsden, whose shopping mall contained a chain bookstore.

After she retired, Shaul’s grandmother harvested pecans, selling small bags of nuts to boost her monthly pension. With that money, she’d take her granddaughter to the bookstore, opening the world to the future English professor through pages of classic literature. Few books were off limits. They bought “Bulfinch’s Mythology,” Edith Hamilton’s “Mythology,” Homer’s “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey,” and Frances Hodgson Burnett’s “The Secret Garden.” She devoured books discarded by college students who moved in and out of the rental homes her parents owned near Snead State Community College. That she meandered into the story boards of graphic novels may explain how easily she embraced the quirkiness of pop culture later in life.

“I loved books and I loved reading,” Shaul said. “My sister is 10 years older than I am, and so I would go for a lot of her books, which weren’t necessarily age appropriate; it was a lot of Judy Blume. I read ‘Helter Skelter’ when I was pretty young. I read anything I could get my hands on.” Storytellers dominate her family tree, she said, the sort of Alabamians who will “stay at a dinner table for four hours swapping stories and everything.” It’s no surprise, then, that the voracious reader has written a book, “Midnight Cry: A Shooting on Sand Mountain,” which she says features a bootlegger and a sheriff and the bootlegger’s 16-year-old son and multiple trials. She’s looking for a publisher.

“I grew up with stories, and there was a story I’d always be fascinated by — a shooting that happened up on Sand Mountain in 1951,” she said. “I heard various permutations of it and relatives would talk about it a lot. People had very definite opinions about it, and it depended whether you were from up on the mountain or down off the mountain, down in Guntersville and Arab and places like that.”

Given her expertise, Shaul carries a strong belief in the importance of studying literature, particularly American literature, in 2022. She tells students in her classes that “in order to participate in the dialogue of citizenry, you need to understand the texts that have woven in a lot of these ideas. Not all of them are legal documents. Some of them are just stories.” And as an Alabamian, her explanation of Southern writers’ relevance touches on the region’s complicated past.

“There’s a love of place and a recognition of great beauty, and not just in terms of the flora, or the fauna, or the landscape, but in traditions and legacies that can represent the highest impulses of humanity,” she said. “In the South, where a large percent of the population didn’t have the material means to pass down a legacy, they didn’t have large swaths of land, they didn’t have chests of silver or cut glass or crystal punch bowls, but they had stories.”

It’s altogether fitting, then, that her favorite book is the Kentucky-born Warren’s “All the King’s Men.” She has re-read it every year since turning 21, usually in the summer. Why? “Because it asks the big questions. It asks about the nature of knowledge. Is it better to know and suffer, or not to know and suffer and not understand why you’re suffering?”

There is no Funko Pop! of Warren on Shaul’s shelves. But she can easily imagine what students think when they visit her office, a space that mixes writers like Warren with the frivolity of toy figurines.

“That I like pop culture and that I have a sense of whimsy,” she said. “And that I think that is fun.”