Story: Phillip Tutor | Photos: Submitted

‘John Lewis: Good Trouble’ offers amazing insight into congressman’s legacy

When U.S. Rep. John Lewis died in 2020, he bequeathed to the world a complex and inspiring legacy that serves as a testament to dogged nonviolent opposition and a roadmap of America’s civil rights movement.

Beaten on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge, attacked alongside other Freedom Riders by the Ku Klux Klan, arrested for protesting racial injustices, Lewis earned the sobriquet of “the conscience of Congress” during his 33-year career in Washington.

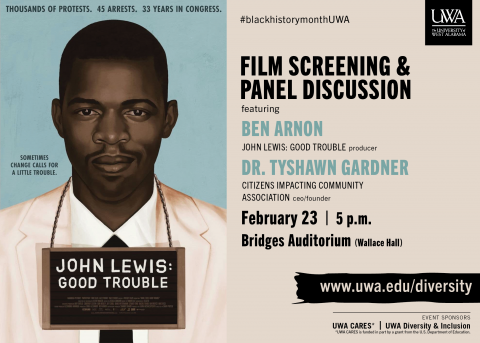

That legacy flows throughout “John Lewis: Good Trouble,” the 2020 documentary by producers Ben Arnon, Erika Alexander, Laura Michalchyshyn and Dawn Porter. In recognition of Black History Month, the University of West Alabama will hold a screening and panel discussion of the 96-minute film on Feb. 23 at Wallace Hall’s Bridges Auditorium. The screening begins at 5 p.m. and is open to the public.

“‘Good Trouble’ tells the inspiring story of late Congressman John Lewis, an American hero who spent his life fighting for voting rights and racial justice,” said Dr. B.J. Kimbrough, UWA’s chief diversity officer and dean of the School of Graduate Studies. “This year, for our annual Black History Commemoration, UWA has embraced the theme, ‘Honoring the Past, Inspiring the Future.’ Through this film, the UWA community will be able to reflect on its role as a hub for civic engagement and inspire future generations to do something that matters and make good trouble when necessary.”

The panel discussion will feature Arnon, co-founder of Color Farm Media, and Dr. Tyshawn Gardner, senior pastor of Plum Grove Baptist Church in Tuscaloosa, who serves as vice president of student affairs at Stillman College, teaches adjunct courses at Samford University’s Beeson Divinity School, and is chief executive officer of the Tuscaloosa-based Citizens Impacting Community Association nonprofit.

After Lewis, a Georgia Democrat, passed away at the age of 80 on June 17, 2020, he became the first Black lawmaker to lie in state in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol — a visual symbol honoring the man whose skull was fractured by white people violently opposed to Black Americans’ quest for voting rights and societal equalities.

One of the many benefits of screening “John Lewis: Good Trouble” on American campuses, Arnon said, is the broadening of students’ knowledge of the congressman’s legacy and political impact. Today’s campuses feature students well aware of Lewis’ life. But not all do, he said.

“I think that there are some people who actually don’t know much about Congressman Lewis at all, and some people, surprisingly, have never even heard of him,” Arnon said. “And that always surprised me a little bit. But when they see the film, actually, I think that they realize how important his legacy is.”

Filmed before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the documentary grew from the merging of two distinct projects and existing relationships between Lewis’ office, Porter and Color Farm Media’s founders. Arnon and Alexander had campaigned with Lewis for Hillary Clinton’s presidential bid. Porter had produced the Netflix film, “Bobby Kennedy for President,” and embarked on her own Lewis documentary that carried the support of CNN Films.

Conversations between Color Farm Media and the congressman’s Atlanta office connected Arnon and Alexander to Porter, who was “totally on board” with the collaboration, Arnon said, and agreed to direct the film.

“Dawn Porter has incredible experience directing and producing films, and she has a whole team of people that she loves to work with, like the cinematographers and the editors,” Arnon said. “So what we really brought us value was in that we had these relationships. Any congressional office is not necessarily easy to navigate or to work with, and there’s a lot of difficulties and challenges in terms of scheduling a film and shooting with them because it’s a moving target.”

For viewers familiar with Lewis’ legacy, it is the access given to the documentarians that resonates throughout “John Lewis: Good Trouble.” Interspersed with familiar scenes of the congressman on Capitol Hill and at campaign events are glimpses of Lewis reading the morning newspaper in his Atlanta home; on drives through his Alabama hometown of Troy; walking the grounds of his family’s farm; and interviews with his siblings.

One poignant moment happens when Henry Louis Gates Jr., the Harvard University professor who hosts PBS’ “Finding Your Roots,” recounts telling Lewis that researchers had determined that his great-great grandfather had registered to vote just two years after the end of the Civil War in 1867.

The end of Reconstruction and subsequent voter-suppression legislation in Southern states prevented other Lewis family members from voting — until Lewis did so nearly a century later.

“I guess it’s in my DNA,” Lewis said.

Since its release, “John Lewis: Good Trouble” has been seen worldwide and screened on myriad campuses, including a number of Historically Black Colleges and Universities. But Arnon, a graduate of Emory University in Atlanta, is thrilled that UWA is bringing the film to its Livingston campus.

“Obviously, Alabama is a critically important state with respect to this film,” Arnon said. “That’s where John Lewis was from. His family is still there. And in western Alabama, really close to Mississippi, just to be frank, there’s still an enormous amount of racism (in the region). There’s enormous amount of voter suppression.

“But what we do see is that there’s also folks who are leaning into better understanding the perspective of John Lewis and his mission to create a beloved community. I do believe in that. I believe that is a possibility. And one of the keys to sort of moving beyond some of the challenges that we face in the nation is exposure. It’s exposure to other people, people that might not look like yourself. It’s exposure to people who come from different religions to different backgrounds in general.”

Through this film, the UWA community will be able to reflect on its role as a hub for civic engagement and inspire future generations to do something that matters and make good trouble when necessary.”

— Dr. B.J. Kimbrough, UWA’s chief diversity officer

Filmmaking and storytelling, Arnon said, can empower negative stereotypes, or it “could really help people to understand the world in different ways and to understand other people,” the latter of which is baked into the Lewis documentary.

As a medium, documentary films have value as entertainment; after all, documentaries that vary widely in quality and tone are prevalent on streaming services such as Netflix and Hulu. But the producers of “John Lewis: Good Trouble” anticipate the film attaining an “evergreen status” that affirms its role as a teaching tool. That Lewis enjoyed the documentary — “He cried and really loved the film,” Arnon said — gives it a further patina of expectation.

“Hopefully it is one of those films that people view repeatedly over time,” Arnon said, “but also that colleges, universities and other schools do lean on to teach about the importance of voting rights, to teach in political science classes, to teach in human rights classes, teaching all kinds of different classes. That’s definitely something that we were hoping for. And so far, the reception has probably been as good as we could have expected.”