Story: Phillip Tutor

Ceremony at UWA Auditorium will highlight inductees’ impressive lives and legacies

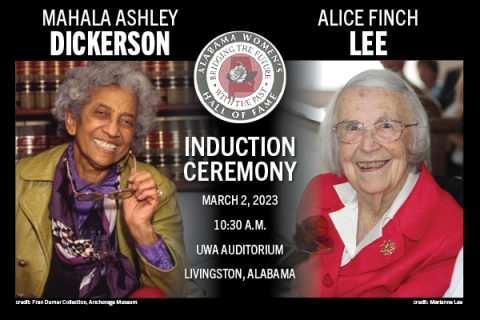

Through perseverance and resolve, attorneys Alice Lee and Mahala Dickerson challenged entrenched social barriers, earned pioneer status and left legacies rooted in gender and racial equality.

Their induction this spring in the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame is, in essence, a celebration of firsts for two standouts in the field of law. Lee, sister of celebrated author Harper Lee, passed the State Bar exam in 1943 and became one of Alabama’s first female lawyers. Five years later, Dickerson followed that path and became the state’s first Black female lawyer.

“One of their similarities is that they’re both definitely trailblazers for women as a whole, and in the case of Miss Dickerson, for African-American women as well,” said Dr. Valerie Burnes, a University of West Alabama history professor and the Hall of Fame’s executive secretary. “There wasn’t a point to induct two lawyers. It just worked out that way.”

The induction ceremony will take place at 10:30 a.m. on March 2 at the UWA Auditorium in the Math and Science Building. The event is free and open to the public, but reservations are required for the luncheon afterward. Luncheon tickets are $50. For information, email Burnes at vburnes@uwa.edu or call (205) 652-3856.

Lee, who died in 2014 at the age of 103, will enter the Hall of Fame alongside her late sister, who was inducted in 2019. The Lees will represent the third familial group among the Hall’s 97 inductees, joining Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald and her daughter, Frances Scott Fitzgerald Smith, and Julia Strudwick Tutwiler and her niece, Martha Strudwick Young.

Born in Monroeville in 1911, Lee attended Huntington College in Montgomery and worked for her father’s newspaper, The Monroe Journal, before becoming president of the Monroeville Business and Professional Women’s Club and accepting a job with the Internal Revenue Service in 1937. Her decision two years later to attend night classes at the Birmingham School of Law and enter a profession wholly dominated by men shaped the rest of her life. After graduating, she joined her father’s law firm, where she used knowledge gained at the IRS to become a renowned expert in tax law.

She didn’t retire until 2011 at the age of 100, earning her the distinction of presumably being the oldest practicing female attorney in the United States at the time.

Outside of her work in tax law, Lee forged a reputation in two unrelated activities — her sister’s renowned privacy, and her dedication to the United Methodist Church.

The success of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” published in 1960, made Harper Lee a household name among U.S. novelists and a prime interview request for journalists. As her sister’s attorney, Alice Lee was well-known as the guardian of the author’s almost iron-clad stance on privacy.

In a series of leadership posts, Lee became a trendsetter among the traditional structure of the church and other faith-based organizations. She was a woman of firsts: the first to lead the complete delegation of the United Methodist Church’s General and Jurisdictional Conference; the first to chair the Alabama-West Florida Council on Ministries; the first to chair the Board of Directors of the United Methodist Church’s Children’s Home. A charter member of the Alabama-West Florida United Methodist Foundation’s Board of Directors, she also served on the General Conference Committee on the Episcopacy and chaired the Andalusia District Committee on the Superintendency. Additionally, she taught Sunday school at Monroeville United Methodist Church for more than half a century.

Outside of the church, she was the first woman to serve on the Monroeville City Planning Commission, spent three decades as the director of the Monroe County Bank, and was inducted in 2012 into the Alabama Academy of Honor.

“She’s worthy of induction, regardless of her sister,” Burnes said.

Like Lee, Dickerson, who died in 2007 at the age of 94, also established a life and legacy that eclipsed the societal and professional norms of her day.

Born into deeply segregated Alabama near Montgomery, Dickerson’s determination took her to Nashville, where she graduated with honors from Fisk University, and to Washington, D.C., where she enrolled in Howard University’s law school. After passing the Alabama State Bar in 1948, she began practicing in Tuskegee and Montgomery. A move to Indiana in 1951 allowed her to become the second Black woman admitted to that state’s Bar.

Dickerson’s career shifted dramatically in 1958 when a vacation to the Alaska territory convinced her to relocate to the future 49th state. (Alaska didn’t gain statehood until January 1959.) It was in the nation’s northernmost state that Dickerson gained prominence and established her own resume of firsts. She became Alaska’s first female Black homesteader; she passed the Alaska State Bar and became that state’s first Black female attorney; and in 1983 she became the first African-American named president of the National Association of Women Lawyers. Back in the South, the Alabama State Bar in 2006 awarded Dickerson the Maud McClure Kelly Award, given each year to one of the state’s outstanding female attorneys.

In Anchorage, Dickerson’s lengthy law practice often specialized in cases regarding civil rights, worker’s rights and women’s rights. She routinely accepted pro bono cases from low-income clients. On appeal, she won a celebrated equal-pay case filed by a female professor at the University of Alaska.

Officials with the Alaska Women’s Hall of Fame, which inducted Dickerson in 2009, included a self description of her law career in their ceremony.

“I have described myself as an attorney for the hopeless, borrowing the title from a book I once read on the life of Clarence Darrow, in which he was described as ‘Attorney for the Damned,’” Dickerson once wrote.

The Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame was established in 1970 to honor the lives of outstanding women from the state of Alabama. Inductees must be deceased for two years and be from or affiliated with Alabama. Women to be inducted are selected by unanimous vote of the board of directors of the AWHF. The board is from a cross section of the state and represents broad areas of interest. To nominate a woman for this honor, use the printable FORM and email to: alabamaWHF@gmail.com.

The University of West Alabama is home to the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame. Previously housed at Judson College until the school’s closure in 2021, the Hall is governed independently, and neither membership nor honors of the AWHF are determined by the University.