Story: Phillip Tutor | Photos: Betsy Compton

Johnson adores extragalactic astronomy — and teaching, too

On Alabama nights when clouds didn’t shroud the stars, Lucas Johnson and his father would haul a powerful telescope from their basement into an open space and explore the heavens. They lived “in the middle of nowhere,” a bit south of Decatur, where light pollution was rare as a neighborhood hockey game. “You can’t help but walk outside at night and see it’s beautiful — fireflies lighting, bugs, crickets and frogs,” Johnson said. “But then you look up and you just see everything. The skies were phenomenal.”

It was there, up above, that Johnson and his father, a physicist who worked in Huntsville, would gaze at far-away galaxies beyond the Milky Way. They’d search for giant dust clouds called nebula, myriad dwarf planets and supernova remnants, the carcasses of exploded stars. Johnson was only 6 years old when he first peered through the telescope, hardly old enough to grasp the enormity of what he saw. But he was mesmerized.

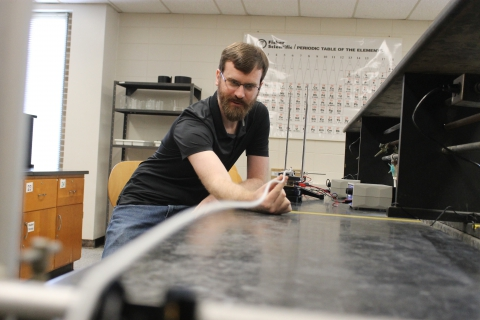

Today, Johnson is 32 and in his third year as an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at the University of West Alabama. In a sense, he is still the grade-school kid looking skyward at points of light under a pristine Alabama nighttime sky.

He grins and blames his father.

“I was asking, ‘What’s this?’, as any kid does, right? ‘What is this? What is that? How does it work?’” Johnson said. “My dad’s always been about feeding that desire for knowledge, and he enjoys space a lot, too, obviously.” A seminal moment happened when Johnson, curious and perhaps a bit precocious, peppered his father with another question: “How does a star work?”

His father said it was astrophysics, the quest to understand the universe.

“He explained it a little bit for my 7-year-old brain,” Johnson said, “and I said, ‘I want to do that.’”

At UWA, the erstwhile child stargazer teaches courses in physics and astronomy in the Department of Physical Sciences. His research concentrates on galaxy groups and clusters. He’s still asking questions: Where did galaxy groups and clusters come from? How did they form? Why are they where they are? And what do distant groups and clusters say about our galaxy?

His interest in extragalactic astronomy — the study of galaxies outside of Earth’s — is an offspring of childhood nights spent exploring worlds the human eye can’t easily see. His voice tenses with excitement when describing telescopes aimed beyond the Milky Way. It takes him, as it always does, to his happy place.

To the stars.

“If you go out just a little bit in space distance, you can find these beehives of galaxies that have hundreds of thousands of individual galaxies all orbiting and smashing and crashing into each other,” he said. “It’s a train wreck, and it’s really cool to look at.”

As passionate as Johnson is about astronomy and physics, his career path could have resembled the fictional characters in “The Big Bang Theory,” the popular sitcom that followed four socially awkward and uber-intelligent science and science-fiction geeks who worked at the same university. In the show, the characters concentrated on research and rarely taught classes.

“This is what I was meant to do. This is what gets me up in the morning. The research is fun. Learning new things is always exciting, but it’s the people. It’s the giving of information to people who didn’t know it before.”

— Dr. Lucas Johnson

That’s where Johnson, the son of a teacher, strays from astrophysicist Rajesh Koothrappali and his “Big Bang” colleagues. Education matters to him. With his mother, who recently retired from a third-grade classroom, “everything was a teachable moment,” he said, his childhood immersed in his father’s science lessons and his mother’s commitment to learning. While studying at the University of Alabama, he eventually faced a fateful decision: Choose a career largely in research or in the classroom.

He chose the latter.

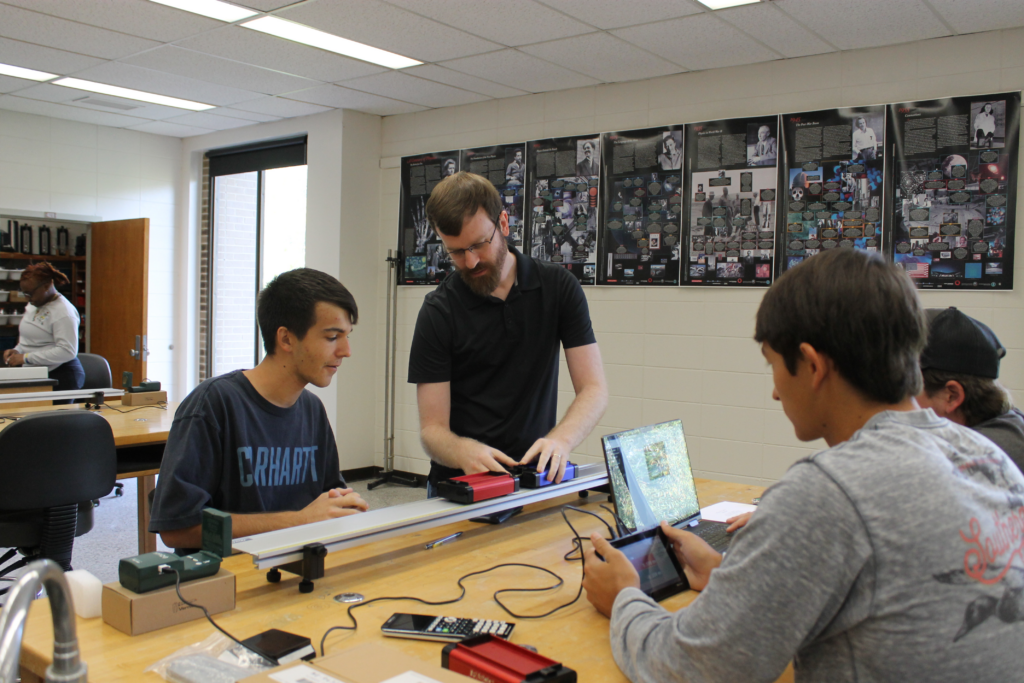

“That was in the back of my mind when I entered college, because when I first declared my major in physics, that’s what I thought my life was going towards, the research side,” he said. “But in my junior or senior year, I thought I should think about being a professor, being an excellent educator, and not just solely focusing on research.” It wasn’t until he taught classes and astronomy labs as a graduate assistant that his choice solidified. He wanted to teach and do research, his goal to help raise science literacy among his students.

“This is what I was meant to do. This is what gets me up in the morning,” he said. “The research is fun. Learning new things is always exciting, but it’s the people. It’s the giving of information to people who didn’t know it before.”

The recent birth of private space exploration and renewed discussions about future moon landings broach a delicious query: Would Johnson welcome an opportunity to go to space and gain a better view of what he’s explored since elementary school?

In a word or two, probably not. But it’s complicated.

“I know just enough about how everything works to be scared, but not enough to feel safe,” he said. But then he pondered the hypothetical a second time and mused about the safety record of the International Space Station, which has been in orbit since 1998. “If I was offered the opportunity, I would seriously consider doing it just because of how unique it was and how important or impactful that would be in a person’s life. But I’m not going to seek it out.”

Instead, he’s content to keep researching distant galaxies and offering his knowledge to students at UWA. Scientific discoveries that lit his mind as a child still do today.

“It’s fascinating,” he said. “I love it.”